Diaspora

The Italian syndrome is spreading to Eastern Europe, Moldova

Reading Time: 9 minutes There are roughly 90,000 Moldovans living in Italy – with numbers growing fast, as shown by a recent report by Caritas-Migrantes. Among the many difficulties of living abroad, one problem is spreading very quickly: the Italian syndrome, a depressive form that affects illegal immigrants and their children

By Laura Delsere

There are roughly 90,000 Moldovans living in Italy – with numbers growing fast, as shown by a recent report by Caritas-Migrantes. Among the many difficulties of living abroad, one problem is spreading very quickly: the Italian syndrome, a depressive form that affects illegal immigrants and their children.

Being an illegal immigrant can make your soul sick. Not only it means not having access to basic services or not being able to rent a house, but also “feeling persecuted and spied upon – says Tatiana Nogalic from Assomoldave, an Italian association for Moldovan immigrants, who deals thoroughly with this problem – It also means not getting out of the house for months on end because a small oversight can be fatal, and being forced to become isolated for fear of being caught by the police. In the end, it means loosing contact with reality. I hope Moldovans won’t have to pay the same price paid by many Romanian and Filipino workers, who have to be cured from the “Italian Syndrome” once they’re back in their own country. This is how this combination of debilitating mental illnesses is called. It includes delusions of being persecuted and abused as well as obsessions related to the work carried out in Italy. “I know a number of my fellow citizens who, due to the habit of living in fear in Italy, when they are back home for a holiday turn pale at the mere sight of a policeman” adds Ms Nogalic.

But the “Italian Syndrome” can also take up a different shape back in the home country. In Moldavia it still hasn’t affected adults as it did in Romania, where last Christmas, when the migrants left after their temporary family reunion for the Christmas holidays, there was a high number of self-harm episodes and suicide attempts – so many that they caught the attention of the media. In Moldavia it mainly affects the under-age sons and daughters of the immigrants, who are left alone, often in an empty house or with grandparents too old to look after them. “In Moldavia there is no ‘connecting group’ left between the generations, only elderly people, children and very young kids are left in the country – explains Tatiana Nogailic – As a consequence, the abandoned under-age kids develop an acute depressive syndrome. This too, according to the newspapers in Chisinau, can be called “Italian Syndrome”. It makes the children anxious, apathetic, and often aggressive due to a lack of reference points. “Elderly people, despite all the affection they can offer, cannot substitute a parent. Nor can they help the children understand a world that is changing extremely fast” as explained by some Moldovan mothers. In rural areas more than half the children live alone or with their grandparents. “It’s an issue that affects our mass emigration and national present right at the heart” says Nogailic, also because these children are then exposed to increased risks of becoming street children or precocious emigrants. This crude reality of the constant feeling of absence experience by the youngest generation has been depicted in a film released in December 2008, which has already won many awards in Europe.

‘Goodbye’, directed by Moldovan director Valeriu Jereghi, which won the Gran Prix Forum Euroasiatic Moscova, is the story of two brothers who are left alone while their parents are abroad. “The film split the opinion in two in Moldavia, where it has very strong supporters and very strong opposers” confirms Ms Nogailic. The same happened with “Bycicle Thieves” by Vittorio De Sica in Italy in the aftermath of the war, just to quote a similar episode. At the heart of the Moldovan film is Italy, and the children that De Sica would have loved. Like in the melancholic close up of the child’s face as he listens to “O Sole Mio” without understanding the words, but knowing it comes from a world from which he is longing his mum will return soon. The film has been screened in Venice and Rome, during meetings about the Moldovan Diaspora. In response to those who accuse him of using a serious national problem for personal gain, Jereghi last month organised a week of free screenings of his film in a central cinema in Chisinau. “People came all the way from the countryside by bus to see it” Tatiana Nogailic says. L.D.

Italy represents a European junction for the Moldovan diaspora. Moreover, the number of immigrants from the banks of the rivers Dnester and Prut is growing at double the speed of that of immigrants from other countries, thus making the Moldovan community the tenth in the country, after the Romanian and Ukrainian ones. Rome has become the second European city for number of Moldovan citizens, after Moscow: the latter has 145,000, while Rome has 12,800, followed by. St Petersburg (more than 9,000), Istanbul (8,000), Odessa (7,650), and Milan (5,800). The most up-to-date profile of this community is offered by the report ‘Moldovan citizens in Italy’, carried out by Caritas and Fondazione Migrantes, in collaboration with the Moldovan Embassy in Rome.

Nowadays there are almost 90,000 Moldovan citizens in our country. Yet, the most impressive thing are the growing numbers in the last ten years: from roughly 4,000 in 2001 they reached 38,000 in 2004, and by 2008 the number of Moldovan immigrants living in Italy has grown by a third (+30,4%), compared to an average growth of +13,4% in the general foreign population in Italy. Women are the pioneer immigrants. They mainly move towards the Mediterranean area (Italy, Spain) to work as carers, so much so that they currently make up 67% of the whole community. Moldovan men, on the other hand, mainly move to Russia, Romania, Ukraine, or Israel.

The second generation grows

Moldovan migrants are increasingly oriented towards moving to Italy permanently. According to the figures offered by the report, nowadays 5% of the community was born in Italy, roughly 2000 newborns in 2008. And roughly 15% of the children are enrolled in Italian schools. “Schools and universities are strategic places for the integration of the younger generation”, as explained by some girls under 30 part of the association “Dacia”, dealing with the Moldovan diaspora in Italy. And they surprisingly mention above all the religious universities, like the one called Angelicum, where Karol Wojtyla studied when he was 20. “The world ‘clandestine’ shouldn’t have been born in this country, cradle of the humanistic culture” state some Moldovan university students.

Churches represent an important reference point for adults. “This is where we can preserve our history, values, language, but also our faith in human rights” as explained by some activists of the non-profit organisation ‘San Mina’, which defends the civil rights of Moldovan citizens n Italy. Cultural development is a very important achievement, but it “inevitably creates a gap between parents and their kids, who feel part of the Italian culture in every respect”, according to the report by Caritas and Migrantes. “The result is that often the second generation doesn’t want to move back to their homeland”. And they end up in a sort of no-man’s-land: for them, “caught in between their homeland and an incomplete sense of participation in the new society – according to the report, obtaining Italian citizenship and nationality will be decisive”.

The new Moldovans from Lazio and Veneto

There are two “Moldovan capitals” in Italy: Rome (and the Lazio region) and Padua (in Veneto). They represent the areas with the highest concentration of Moldovan migrants, with almost 8,000 residents in total. They are employed mainly in the sector of home caring (32%), building (12%), and services (11%). According to the map offered but Caritas-Migrantes, the highest concentration is in the North West (35.2%), followed by the North East (27%) and the Centre (25.1%). The concentration is lower in the South (9.1%) and on the isles (3.7%). But their path is constantly uphill, according to the voices of the diaspora. “The renewal of the residence permit is the main problem, and it is becoming more and more difficult to obtain” explains Natalia Moraru, president of the association ‘Dòina’.

The situation is substantially better for regular immigrants, even though they often occupy positions below their level of education: in Rome, for example, 70% of Moldovan immigrants have a degree (of which 5% has two degrees or a Ph.D.), 30% has a secondary school diploma or a professional qualification. But only 30-35% manages to achieve a position suited to their level of education, and the most common jobs are the manual ones in the services sector, or in families and hotels. Despite the many associations constituted so far, the main space of socialisation for Moldovan immigrants remains the street: the squares in front of the churches they attend, often the ‘work markets’, and the bus stations (in Rome, at Tor di Valle), since the bus has become the symbol of commuting between Italy and Chisinau. According to many, in the stations the trips are controlled by the racket of drivers and transport companies, who have complete control over the tariff and the goods sent, which often include parcels full of cash. Sometimes they get ‘stolen’ and in order to get them back a ransom has to be paid – as happened to a lady whose 8,000 Euro of savings disappeared.

The Moldovan diaspora: a citizen in 4 lives abroad

The big wave of migration from Moldavia started in 1999, the year after the Russian default during which the level of poverty reached its peak in the country: 80.9% in the small villages, 76.2% in the rural areas, 50.4% in the big cities. During those 12 months 100,000 people left. In 1992 a further push had come from the conflict with Russia in Transnistria, an area with a high concentration of factories, which increased the occupational catastrophe even further.

Today, one out of four of the 4.2 million Moldovan citizens lives abroad. The republic has also entered the worldwide top list of countries with the highest level of remittances in proportion to the population: almost a third if their national GDP (36%, equal to 1.4 billion dollars in 2008). The money is often sent via informal channels, very seldom using banks. The total amount of remittances sent from Italy during the same year was of 54.5 million Euro. According to the report, “if the whole family is in Italy Moldovan immigrants send an average of 400-600 Euro back to their home country, while if husband and children are still in Moldavia the amount can reach 10,000 Euro per year”. The average figure is of 7-8,000 Euro per year, “used mainly to provide for the family, pay for their children’s education, buy a house”.

Among the most disadvantaged when it comes to getting a EU visa

Apart from poverty, unemployment, and low wages, nowadays some of the main causes of emigration are “the political instability, corruption and the denial of human rights – as explained by the analysts that carried out the 2009 report – At the moment Moldovans are among the most disadvantaged groups as far as getting a EU visa is concerned”. Just think that from 2007 (when Romania entered the EU) until 28th January 2009 (when the Italian diplomatic head office in Chisinau started issuing visas), Moldovan emigrants used to go to the Italian embassy in Bucharest in order to apply for visas to travel to Rome, as they did for Spain or Slovenia. In order to obtain a visa for Greece or Cyprus they used to travel to Ukraine instead. “A gold mine for criminal organisations, to say the least”.

It is sufficient to ask migrants themselves to obtain up-to-date tariffs: today a visa for Italy costs 4,500 Euro, and it is issued by the not-so-transparent Moldovan job agencies, which also prepare the candidates for the interview at the embassy (“be natural”, “don’t blush”, “repeat exactly what we tell you”), while in 2004 the middlemen could only ask for 2,500 Euro.

The majority of Moldovan immigrants arrive in Italy with a tourist visa, but the percentage of victims of human trafficking is still among the highest in Eastern Europe. 919 were assisted in Italy over the last few years, according to the Report, which makes this community the most vulnerable after the Nigerian and Romanian ones.

Bureaucracy, the main obstacle to building a life in Italy

“Once here our emigrants need most of all information and not to be left alone” explains Tatiana Nogailic, president of Assomoldave. “Access to information is vital for an immigrant. So much so, that whenever a new law is approved we rely not only on our blog to spread the news, but also on text messages. We send up to a thousand of them”.

Which are the main difficulties for Moldovan immigrants? “It depends on whether they hold a visa or not. Those who do include the Romanian ones, while the ones that don’t are considered outlaws under the new “security measures”. Personally, I lived in fear while I was waiting for my visa to be first issued and then renewed. The first time for one and a half years, the second for two. While we are illegal we are forbidden from going back home, and this makes us non-existent”. As Ms Nogailic adds “in general the insecurity never ends due to the countless laws and the many different interpretations they’re subject to. Just think about the certificate of permanent address required to obtain a residence permit: instead of a single regional law, each municipality in Rome has different procedures, from 2 to 12 certificates”.

More and more hidden: how the latest mass regularisation failed

What changed after the late mass regularisation? “It was only a partial success, we received only half of the applications we expected – says Ms Nogailic – One of the reasons behind the failure is the fact that employers started to lay employees off shortly before the act of indemnity. For three reasons: the excessive costs for the employer, fears related to bureaucracy involved in the application procedure, and lastly the availability on the market of low cost commuters. But the main fault of the law was regularising those who had only one employer, thus leaving out for example all the domestic helpers who worked for more than one family. We all know that these women are still working, even if with more disadvantages. But even if they worked more than 12 hours per day and were willing to cover all the costs, they weren’t given the possibility to become regular. We reported with no success what was happening to the Provincial Governor Mario Morcone, head of the Department for Civil Liberties and Immigration of the Ministry of the Interior”. But recently the governor himself, while presenting the results of the mass regularisation, admitted that “there are still many illegal immigrants and the regularisation should be extended”.

Society

“They are not needy, but they need help”. How Moldovan volunteers try to create a safe environment for the Ukrainian refugees

At the Government’s ground floor, the phones ring constantly, the laptop screens never reach standby. In one corner of the room there is a logistics planning meeting, someone has a call on Zoom with partners and donors, someone else finally managed to take a cookie and make some coffee. Everyone is exhausted and have sleepy red eyes, but the volunteers still have a lot of energy and dedication to help in creating a safe place for the Ukrainian refugees.

“It’s like a continuous bustle just so you won’t read the news. You get home sometimes and you don’t have time for news, and that somehow helps. It’s a kind of solidarity and mutual support,” says Vlada Ciobanu, volunteer responsible for communication and fundraising.

The volunteers group was formed from the very first day of war. A Facebook page was created, where all types of messages immediately started to flow: “I offer accommodation”, “I want to help”, “I want to get involved”, “Where can I bring the products?”, “I have a car and I can go to the customs”. Soon, the authorities also started asking for volunteers’ support. Now they all work together, coordinate activities and try to find solutions to the most difficult problems.

Is accommodation needed for 10, 200 or 800 people? Do you need transportation to the customs? Does anyone want to deliver 3 tons of apples and does not know where? Do you need medicine or mobile toilets? All these questions require prompt answers and actions. Blankets, sheets, diapers, hygiene products, food, clothes – people bring everything, and someone needs to quickly find ways of delivering them to those who need them.

Sometimes this collaboration is difficult, involves a lot of bureaucracy, and it can be difficult to get answers on time. “Republic of Moldova has never faced such a large influx of refugees and, probably because nobody thought this could happen, a mechanism of this kind of crisis has not been developed. Due to the absence of such a mechanism that the state should have created, we, the volunteers, intervened and tried to help in a practical way for the spontaneous and on the sport solutions of the problems,” mentions Ecaterina Luțișina, volunteer responsible for the refugees’ accommodation.

Ana Maria Popa, one of the founders of the group “Help Ukrainians in Moldova/SOS Українці Молдовa” says that the toughest thing is to find time and have a clear mind in managing different procedures, although things still happen somehow naturally. Everyone is ready to intervene and help, to take on more responsibilities and to act immediately when needed. The biggest challenges arise when it is necessary to accommodate large families, people with special needs, for which alternative solutions must be identified.

Goods and donations

The volunteers try to cope with the high flow of requests for both accommodation and products of all kinds. “It came to me as a shock and a panic when I found out that both mothers who are now in Ukraine, as well as those who found refuge in our country are losing their milk because of stress. We are trying to fill an enormous need for milk powder, for which the demand is high and the stocks are decreasing”, says Steliana, the volunteer responsible for the distribution of goods from the donation centers.

Several centers have been set up to collect donations in all regions of Chisinau, and volunteers are redirecting the goods to where the refugees are. A system for processing and monitoring donations has already been established, while the volunteer drivers take over the order only according to a unique code.

Volunteers from the collection centers also do the inventory – the donated goods and the distributed goods. The rest is transported to Vatra deposit, from where it is distributed to the placement centers where more than 50 refugees are housed.

When they want to donate goods, but they don’t know what would be needed, people are urged to put themselves in the position of refugees and ask themselves what would they need most if they wake up overnight and have to hurriedly pack their bags and run away. Steliana wants to emphasise that “these people are not needy, but these people need help. They did not choose to end up in this situation.”

Furthermore, the volunteer Cristina Sîrbu seeks to identify producers and negotiate prices for products needed by refugees, thus mediating the procurement process for NGOs with which she collaborates, such as Caritas, World Children’s Fund, Polish Solidarity Fund, Lifting hands, Peace Corps and others.

One of the challenges she is facing now is the identifying a mattress manufacturer in the West, because the Moldovan mattress manufacturer that has been helping so far no longer has polyurethane, a raw material usually imported from Russia and Ukraine.

Cristina also needs to find solutions for the needs of the volunteer groups – phones, laptops, gsm connection and internet for a good carrying out of activities.

Hate messages

The most difficult thing for the communication team is to manage the hate messages on the social networks, which started to appear more often. “Even if there is some sort of dissatisfaction from the Ukrainian refugees and those who offer help, we live now in a very diverse society, there are different kind of people, and we act very differently under stress,” said Vlada Ciobanu.

Translation by Cătălina Bîrsanu

Important

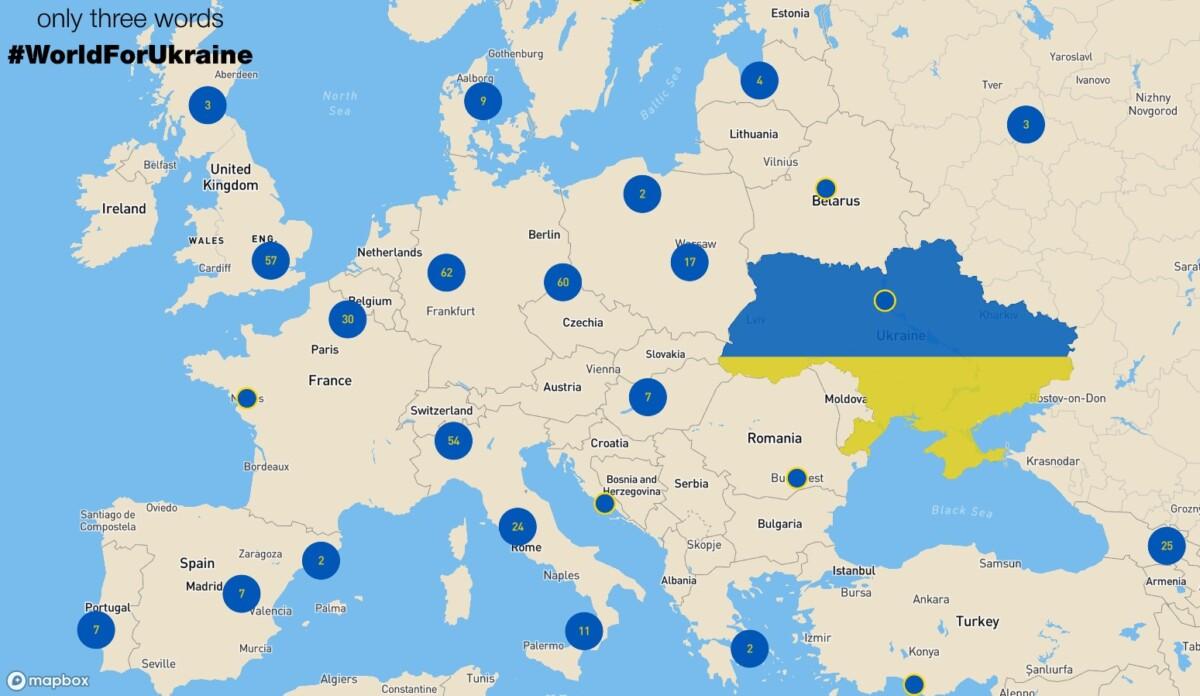

#WorldForUkraine – a map that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against Russian aggression

The international community and volunteers from all over te world have launched #WorldForUkraine as a platform that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against the Russian aggression. In a digital world – it is an interactive map of public support of Ukrainians under the hashtag #WorldForUkraine – rallies, flash mobs, protests around the world. In the physical dimension – it is your opportunity to take to the streets and declare: “No to Putin’s aggression, no to war.”

„Today, along with the political and military support, emotional connection with the civilized world and truthful information are extremely important for Ukraine. The power to do it is in your hands. Join the #WorldForUkraine project and contribute to the victorious battle against the bloodshed inflicted on Ukraine by the aggression of the Russian Federation”, says the „about the project” section of the platform.

Go to the streets — Tell people — Connect and Unite — Become POWERFUL

Volunteers have launched #WorldForUkraine as a platform that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against Russian aggression. In digital world – it is an INTERACTIVE MAP of public support of Ukrainians worldforukraine.net under the hashtag #WorldForUkraine – rallies, flash mobs, protests around the world. In the physical dimension – it is your opportunity to take to the streets and declare: “No to Putin’s aggression, no to war.” There you may find information about past and future rallies in your city in support of Ukraine. This is a permanent platform for Ukrainian diaspora and people all over the world concerned about the situation in Ukraine.

So here’s a couple of things you could do yourself to help:

* if there is a political rally in your city, then participate in it and write about it on social media with geolocation and the hashtag #WorldForUkraine

* if there are no rallies nearby, organize one in support of Ukraine yourself, write about it on social media with geolocation adding the hashtag #WorldForUkraine

The map will add information about gathering by #WorldForUkraine AUTOMATICALLY

Your voice now stronger THAN ever

All rallies are already here: https://worldforukraine.net

Important

How is Moldova managing the big influx of Ukrainian refugees? The authorities’ plan, explained

From 24th to 28th of February, 71 359 Ukrainian citizens entered the territory of Republic of Moldova. 33 173 of them left the country. As of this moment, there are 38 186 Ukrainian citizens in Moldova, who have arrived over the past 100 hours.

The Moldovan people and authorities have organized themselves quickly from the first day of war between Russia and Ukraine. However, in the event of a prolonged armed conflict and a continuous influx of Ukrainian refugees, the efforts and donations need to be efficiently managed. Thus, we inquired about Moldova’s long-term plan and the state’s capacity to receive, host, and treat a bigger number of refugees.

On February 26th, the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Moldova approved the Regulation of organization and functioning of the temporary Placement Center for refugees and the staffing and expenditure rules. According to the Regulation, the Centers will have the capacity of temporary hosting and feeding at least 20 persons, for a maximum of 3 months, with the possibility of extending this period. The Centers will also offer legal, social, psychological, and primary medical consultations to the refugees. The Center’s activity will be financed from budget allocations, under Article 19 of Provision no. 1 of the Exceptional Situations Commission from February 24th, 2022, and from other sources of funding that do not contravene applicable law.

The Ministry of Inner Affairs and the Government of Moldova facilitated the organization of the volunteers’ group “Moldova for Peace”. Its purpose is to receive, offer assistance and accommodation to the Ukrainian refugees. The group is still working on creating a structure, registering and contacting volunteers, etc. It does not activate under a legal umbrella.

Lilia Nenescu, one of the “Moldova for Peace” volunteers, said that the group consists of over 20 people. Other 1700 registered to volunteer by filling in this form, which is still available. The group consists of several departments:

The volunteers’ department. Its members act as fixers: they’re responsible for connecting the people in need of assistance with the appropriate department. Some of the volunteers are located in the customs points. “The Ministry of Inner Affairs sends us every day the list of the customs points where our assistance is needed, and we mobilize the volunteers”, says Lilia Nenescu.

The Goods Department manages all the goods donated by the Moldavian citizens. The donations are separated into categories: non-perishable foods and non-food supplies. The volunteers of this department sort the goods into packages to be distributed.

The Government intends to collect all the donations in four locations. The National Agency for Food Safety and the National Agency for Public Health will ensure mechanisms to confirm that all the deposited goods comply with safety and quality regulations.

The Service Department operates in 4 directions and needs the volunteer involvement of specialists in psychology, legal assistance (the majority of the refugees only have Ukrainian ID and birth certificates of their children); medical assistance; translation (a part of the refugees are not Ukrainian citizens).

According to Elena Mudrîi, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Health, so far there is no data about the number of Covid-19 positive refugees. She only mentioned two cases that needed outpatient medical assistance: a pregnant woman and the mother of a 4-day-old child.

The Accommodation Department. The volunteers are waiting for the centralized and updated information from the Ministry of Labor about the institutions offering accommodation, besides the houses offered by individuals.

The Transport Department consists of drivers organized in groups. They receive notifications about the number of people who need transportation from the customs points to the asylum centers for refugees.

The municipal authorities of Chișinău announced that the Ukrainian children refugees from the capital city will be enrolled in educational institutions. The authorities also intend to create Day-Care Centers for children, where they will be engaged in educational activities and will receive psychological assistance. Besides, the refugees from the municipal temporary accommodation centers receive individual and group counseling.

In addition to this effort, a group of volunteers consisting of Ana Gurău, Ana Popapa, and Andrei Lutenco developed, with the help of Cristian Coșneanu, the UArefugees platform, synchronized with the responses from this form. On the first day, 943 people offered their help using the form, and 110 people asked for help. According to Anna Gurău, the volunteers communicate with the Government in order to update the platform with the missing data.

Translation from Romanian by Natalia Graur