Society

Russians’ experience with Soviet lines blocks rise of civil society today

Reading Time: 4 minutesStanding in line, which Soviet citizens did from three to eight hours every day, formed “not only the worldview but the behavioral strategy” of Soviet citizens, and that socializing experience continu

by Paul Goble

Kuressaare, November 21 – Standing in line, which Soviet citizens did from three to eight hours every day, formed "not only the worldview but the behavioral strategy" of Soviet citizens, and that socializing experience continues to shape the attitudes of post-Soviet Russians and thus make the emergence of a civil society there far more difficult.

In a remarkable article in this week’s "New Times" magazine, Vladimir Nikolayev examines an activity which he argues had such "a powerful socializing impact" on the Russian people that it continues to affect how they think and act even at a time when lines have become a less prominent feature in their lives (newtimes.ru/magazine/2008/issue092/doc-59795.html).

Lines, the Moscow sociologist says, were where people "formed their ideas about the society in which they lived." It was in them that "an individual understood what his compatriots though about themselves and how he (or she) played a role in this system." And lines communicated to those in them just what kind of a struggle for existence they faced.

And perhaps especially important with regards to its continuing impact on the lives of Russians now, he continues, "standing in line was an activity whose outcome was unclear: the Soviet customer could not be certain than when his turn came there would be something left for him."

But lines not only formed the worldview of those who stood in them, they also dictated "a behavioral strategy." Those standing in line were compelled to use force against others in the line or engage in open deception. And every individual in line had to keep track of who was ahead of him and who was behind, lest his own position be threatened.

Such behavior strategies continue to function now, Nikolayev says, as anyone can see who looks at a line not waiting to buy sausages as in the past but to get a passport or a bus. Moreover, even those who were not born in Soviet times follow this pattern because "the older generation by its behavior gives the young a model for emulation."

On the one hand, that means that the attitudes and behaviors learned in Soviet lines will not die out with the first generation or even the second or third. And on the other, these things helped to explain the specific nature of "’wild Russian capitalism,’" a phenomenon very different than its Western counterpart.

The difference between Russia and the West in this regard, the sociologist suggests, reflects the reality that people in Russia "simply do not know other means of living in a competitive milieu, and in this sense, contemporary Russian capitalism as a way of life is a Soviet and in no way a Western product."

Lines, of course, are "a means of organizing the inter-relationship and interaction of people in concrete situations for deficit goods of a material or symbolic character. The main thing in these interrelationships is how people conduct themselves toward others and how they group themselves and with whom they stand up against competitors."

In Soviet times, family members were terribly important because members of one family often had to stand together in order to be in a position to carry away whatever they hoped to get or alternatively to stand in more than one line for goods that the family need. Thus, lines at that time made the family especially important.

Now, Nikolayev writes, "the character of lines has changed because deficits have changed from something universal to something specific." Consequently, people no longer stand in line for almost everything but rather for things like "heart transplants" or "obtaining a passport or a car." And that has changed some things but far from all.

One thing it has not changed, the sociologist says, is the way in which people view the lines: they are "barricades, on one side of which stands a dependent population and on the others, sellers who [are in a position to] take decisions which are important for the buyers."

In this arrangement, the sellers are hated by the buyers, but at the same time, in the Soviet period, "many wanted to become sellers in order to have the magical possibility of participating in the distribution of deficit goods." Now, the same attitudes inform the Russian population with regard to members of the militia or the FSB.

Lines in Soviet times were thus "a wall which separated the people from the government and in this way defined the status of the individual in the state." The only "path to goods and services for the majority of people lay through a single mechanism: the line," and as a result, the line defined who an individual was.

According to Nikolayev, "the link between the line, the people and goods was so clear that a Soviet man, when seeing a line, would say: ‘the people are standing for something.’" That was all the more so because some groups – the party elite and its allies – did not have to stand in line because they got their goods via special stores.

"Soviet life was constructed so that the government [which consisted of these groups] and the people never came into contact," Nikolayev writes. And "in this sense, little has changed." The only difference is that those who did not have to wait in line in Soviet times were part of the nomenklatura, while those who do not have to do so now have money.

And another thing that has not changed, he insists, is the way in which those standing in lines feel toward others. They expend their energy "not in cooperation with one another but in a struggle with one another," and that experience "interferes with the formation of the horizontal ties needed for the formation of civil society."

Indeed, what the line taught in Soviet times and what it teaches now, Nikolayev concludes, is hatred of those in power, hatred of the successful, and the need to behave in whatever way it takes to achieve "egoistic goals." In this sense, he says, "a large part of the Russian population remains Soviet consumers … with all the ensuing consequences."

—-

Paul A. Goble is an American analyst, writer and columnist with expertise on Russia, Eurasia, public diplomacy and international broadcasting. Goble publishes his articles on his blog "Window on Eurasia" (windowoneurasia.blogspot.com).

Society

“They are not needy, but they need help”. How Moldovan volunteers try to create a safe environment for the Ukrainian refugees

At the Government’s ground floor, the phones ring constantly, the laptop screens never reach standby. In one corner of the room there is a logistics planning meeting, someone has a call on Zoom with partners and donors, someone else finally managed to take a cookie and make some coffee. Everyone is exhausted and have sleepy red eyes, but the volunteers still have a lot of energy and dedication to help in creating a safe place for the Ukrainian refugees.

“It’s like a continuous bustle just so you won’t read the news. You get home sometimes and you don’t have time for news, and that somehow helps. It’s a kind of solidarity and mutual support,” says Vlada Ciobanu, volunteer responsible for communication and fundraising.

The volunteers group was formed from the very first day of war. A Facebook page was created, where all types of messages immediately started to flow: “I offer accommodation”, “I want to help”, “I want to get involved”, “Where can I bring the products?”, “I have a car and I can go to the customs”. Soon, the authorities also started asking for volunteers’ support. Now they all work together, coordinate activities and try to find solutions to the most difficult problems.

Is accommodation needed for 10, 200 or 800 people? Do you need transportation to the customs? Does anyone want to deliver 3 tons of apples and does not know where? Do you need medicine or mobile toilets? All these questions require prompt answers and actions. Blankets, sheets, diapers, hygiene products, food, clothes – people bring everything, and someone needs to quickly find ways of delivering them to those who need them.

Sometimes this collaboration is difficult, involves a lot of bureaucracy, and it can be difficult to get answers on time. “Republic of Moldova has never faced such a large influx of refugees and, probably because nobody thought this could happen, a mechanism of this kind of crisis has not been developed. Due to the absence of such a mechanism that the state should have created, we, the volunteers, intervened and tried to help in a practical way for the spontaneous and on the sport solutions of the problems,” mentions Ecaterina Luțișina, volunteer responsible for the refugees’ accommodation.

Ana Maria Popa, one of the founders of the group “Help Ukrainians in Moldova/SOS Українці Молдовa” says that the toughest thing is to find time and have a clear mind in managing different procedures, although things still happen somehow naturally. Everyone is ready to intervene and help, to take on more responsibilities and to act immediately when needed. The biggest challenges arise when it is necessary to accommodate large families, people with special needs, for which alternative solutions must be identified.

Goods and donations

The volunteers try to cope with the high flow of requests for both accommodation and products of all kinds. “It came to me as a shock and a panic when I found out that both mothers who are now in Ukraine, as well as those who found refuge in our country are losing their milk because of stress. We are trying to fill an enormous need for milk powder, for which the demand is high and the stocks are decreasing”, says Steliana, the volunteer responsible for the distribution of goods from the donation centers.

Several centers have been set up to collect donations in all regions of Chisinau, and volunteers are redirecting the goods to where the refugees are. A system for processing and monitoring donations has already been established, while the volunteer drivers take over the order only according to a unique code.

Volunteers from the collection centers also do the inventory – the donated goods and the distributed goods. The rest is transported to Vatra deposit, from where it is distributed to the placement centers where more than 50 refugees are housed.

When they want to donate goods, but they don’t know what would be needed, people are urged to put themselves in the position of refugees and ask themselves what would they need most if they wake up overnight and have to hurriedly pack their bags and run away. Steliana wants to emphasise that “these people are not needy, but these people need help. They did not choose to end up in this situation.”

Furthermore, the volunteer Cristina Sîrbu seeks to identify producers and negotiate prices for products needed by refugees, thus mediating the procurement process for NGOs with which she collaborates, such as Caritas, World Children’s Fund, Polish Solidarity Fund, Lifting hands, Peace Corps and others.

One of the challenges she is facing now is the identifying a mattress manufacturer in the West, because the Moldovan mattress manufacturer that has been helping so far no longer has polyurethane, a raw material usually imported from Russia and Ukraine.

Cristina also needs to find solutions for the needs of the volunteer groups – phones, laptops, gsm connection and internet for a good carrying out of activities.

Hate messages

The most difficult thing for the communication team is to manage the hate messages on the social networks, which started to appear more often. “Even if there is some sort of dissatisfaction from the Ukrainian refugees and those who offer help, we live now in a very diverse society, there are different kind of people, and we act very differently under stress,” said Vlada Ciobanu.

Translation by Cătălina Bîrsanu

Important

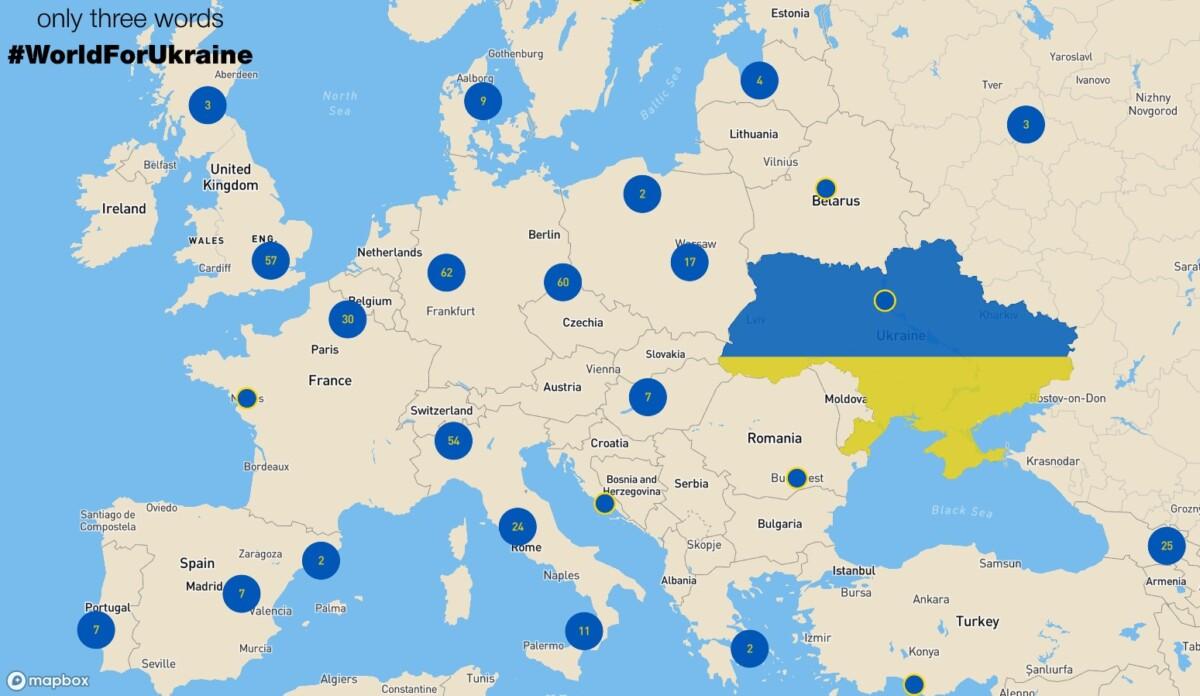

#WorldForUkraine – a map that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against Russian aggression

The international community and volunteers from all over te world have launched #WorldForUkraine as a platform that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against the Russian aggression. In a digital world – it is an interactive map of public support of Ukrainians under the hashtag #WorldForUkraine – rallies, flash mobs, protests around the world. In the physical dimension – it is your opportunity to take to the streets and declare: “No to Putin’s aggression, no to war.”

„Today, along with the political and military support, emotional connection with the civilized world and truthful information are extremely important for Ukraine. The power to do it is in your hands. Join the #WorldForUkraine project and contribute to the victorious battle against the bloodshed inflicted on Ukraine by the aggression of the Russian Federation”, says the „about the project” section of the platform.

Go to the streets — Tell people — Connect and Unite — Become POWERFUL

Volunteers have launched #WorldForUkraine as a platform that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against Russian aggression. In digital world – it is an INTERACTIVE MAP of public support of Ukrainians worldforukraine.net under the hashtag #WorldForUkraine – rallies, flash mobs, protests around the world. In the physical dimension – it is your opportunity to take to the streets and declare: “No to Putin’s aggression, no to war.” There you may find information about past and future rallies in your city in support of Ukraine. This is a permanent platform for Ukrainian diaspora and people all over the world concerned about the situation in Ukraine.

So here’s a couple of things you could do yourself to help:

* if there is a political rally in your city, then participate in it and write about it on social media with geolocation and the hashtag #WorldForUkraine

* if there are no rallies nearby, organize one in support of Ukraine yourself, write about it on social media with geolocation adding the hashtag #WorldForUkraine

The map will add information about gathering by #WorldForUkraine AUTOMATICALLY

Your voice now stronger THAN ever

All rallies are already here: https://worldforukraine.net

Important

How is Moldova managing the big influx of Ukrainian refugees? The authorities’ plan, explained

From 24th to 28th of February, 71 359 Ukrainian citizens entered the territory of Republic of Moldova. 33 173 of them left the country. As of this moment, there are 38 186 Ukrainian citizens in Moldova, who have arrived over the past 100 hours.

The Moldovan people and authorities have organized themselves quickly from the first day of war between Russia and Ukraine. However, in the event of a prolonged armed conflict and a continuous influx of Ukrainian refugees, the efforts and donations need to be efficiently managed. Thus, we inquired about Moldova’s long-term plan and the state’s capacity to receive, host, and treat a bigger number of refugees.

On February 26th, the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Moldova approved the Regulation of organization and functioning of the temporary Placement Center for refugees and the staffing and expenditure rules. According to the Regulation, the Centers will have the capacity of temporary hosting and feeding at least 20 persons, for a maximum of 3 months, with the possibility of extending this period. The Centers will also offer legal, social, psychological, and primary medical consultations to the refugees. The Center’s activity will be financed from budget allocations, under Article 19 of Provision no. 1 of the Exceptional Situations Commission from February 24th, 2022, and from other sources of funding that do not contravene applicable law.

The Ministry of Inner Affairs and the Government of Moldova facilitated the organization of the volunteers’ group “Moldova for Peace”. Its purpose is to receive, offer assistance and accommodation to the Ukrainian refugees. The group is still working on creating a structure, registering and contacting volunteers, etc. It does not activate under a legal umbrella.

Lilia Nenescu, one of the “Moldova for Peace” volunteers, said that the group consists of over 20 people. Other 1700 registered to volunteer by filling in this form, which is still available. The group consists of several departments:

The volunteers’ department. Its members act as fixers: they’re responsible for connecting the people in need of assistance with the appropriate department. Some of the volunteers are located in the customs points. “The Ministry of Inner Affairs sends us every day the list of the customs points where our assistance is needed, and we mobilize the volunteers”, says Lilia Nenescu.

The Goods Department manages all the goods donated by the Moldavian citizens. The donations are separated into categories: non-perishable foods and non-food supplies. The volunteers of this department sort the goods into packages to be distributed.

The Government intends to collect all the donations in four locations. The National Agency for Food Safety and the National Agency for Public Health will ensure mechanisms to confirm that all the deposited goods comply with safety and quality regulations.

The Service Department operates in 4 directions and needs the volunteer involvement of specialists in psychology, legal assistance (the majority of the refugees only have Ukrainian ID and birth certificates of their children); medical assistance; translation (a part of the refugees are not Ukrainian citizens).

According to Elena Mudrîi, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Health, so far there is no data about the number of Covid-19 positive refugees. She only mentioned two cases that needed outpatient medical assistance: a pregnant woman and the mother of a 4-day-old child.

The Accommodation Department. The volunteers are waiting for the centralized and updated information from the Ministry of Labor about the institutions offering accommodation, besides the houses offered by individuals.

The Transport Department consists of drivers organized in groups. They receive notifications about the number of people who need transportation from the customs points to the asylum centers for refugees.

The municipal authorities of Chișinău announced that the Ukrainian children refugees from the capital city will be enrolled in educational institutions. The authorities also intend to create Day-Care Centers for children, where they will be engaged in educational activities and will receive psychological assistance. Besides, the refugees from the municipal temporary accommodation centers receive individual and group counseling.

In addition to this effort, a group of volunteers consisting of Ana Gurău, Ana Popapa, and Andrei Lutenco developed, with the help of Cristian Coșneanu, the UArefugees platform, synchronized with the responses from this form. On the first day, 943 people offered their help using the form, and 110 people asked for help. According to Anna Gurău, the volunteers communicate with the Government in order to update the platform with the missing data.

Translation from Romanian by Natalia Graur