Culture

Climăuții de Jos – an untouched treasure on the banks of Nistru river

Grandma Ana cuts down the corn stalks. She throws the sere corn stalks in the pile on the ground, and the green ones are left standing. In the garden you can also see some pumpkins, a few pepper plants that never gave any fruits and some green tomatoes. The grapes were already picked and pressed, and the tub with must is covered with plastic and a few rugs.

The old woman is accompanied by Ursulică (Little Bear), a small black dog who follows her everywhere. Her daughters live abroad and she was left all alone since her partner died a few years back. This is when she moved to a small annex to the house, where she has a bathroom, a toilet and a small kitchen. She doesn’t need anything more. She only goes into the main house from time to time to check out if everything is alright.

In the small yard you can also find a bed next to a wall, a dog house for Ursulică and a few freshly washed head scarfs hanging out to dry. Ana takes a seat on the bed and tries to get the paint off her fingers after painting the small gate to the garden.

Houses from the past

The house she left uninhabited was built in 1962. She built it with great trouble, because they didn’t have money or materials. “We got rocks from the hills up there, we brought them by cart. We carried them, we built the foundation. And then we built up. Then we put up the ceiling. We had people helping out, we put the roof on. Then, little by little, we started with one room, and then the other. And going on like this till we got old,” tells us Ana. The 78 years old woman likes the new houses better. “Because they’re new!,” she says enthusiastically.

Actually, Ana’s house, the outside plaster aside, is built in a traditional style, representative for Moldovans. It consists of two to three rooms, an entryway, verandah, gable, and an oriel.

The traditional Moldovan house also has a “gallery”. It is actually the facade of the rustic house and marks the passage from the larger, outside area, to the smaller one within the house. The gallery consists of a few classic elements: the porch, the railing and the columns. The porch is the part supporting the gallery. It can be built from wood or stone and placed alongside the main side of the house.

Another important element of the rustic house is the oriel. Similar to the porch, it can be built from wood or stone. The oriel can be closed or open.

Other essential elements are the doors and windows. There are a few categories of doors: single or double doors, with or without window frames.

The old fashioned windows were usually double or triple framed and had shutters. They had a tilting sash called oberlicht.

Source: ”Building and decorative typologies in the vernacular architecture in Moldova” by Vitalie Malcoci, researcher, Institute of Cultural Patrimony.

The wooden gable is still untouched, but in the attic you can see two small holes – for the pigeons, explains Ana. Today, pigeons don’t go into the attic anymore, nor does the old woman. “When I was young, I would climb into the attic and cry, but now…,” Ana jokes. She is resting on her porch overwhelmed by memories. “This is my house, this is my table. What else do you want from me? A glass of wine?,” she asks amused.

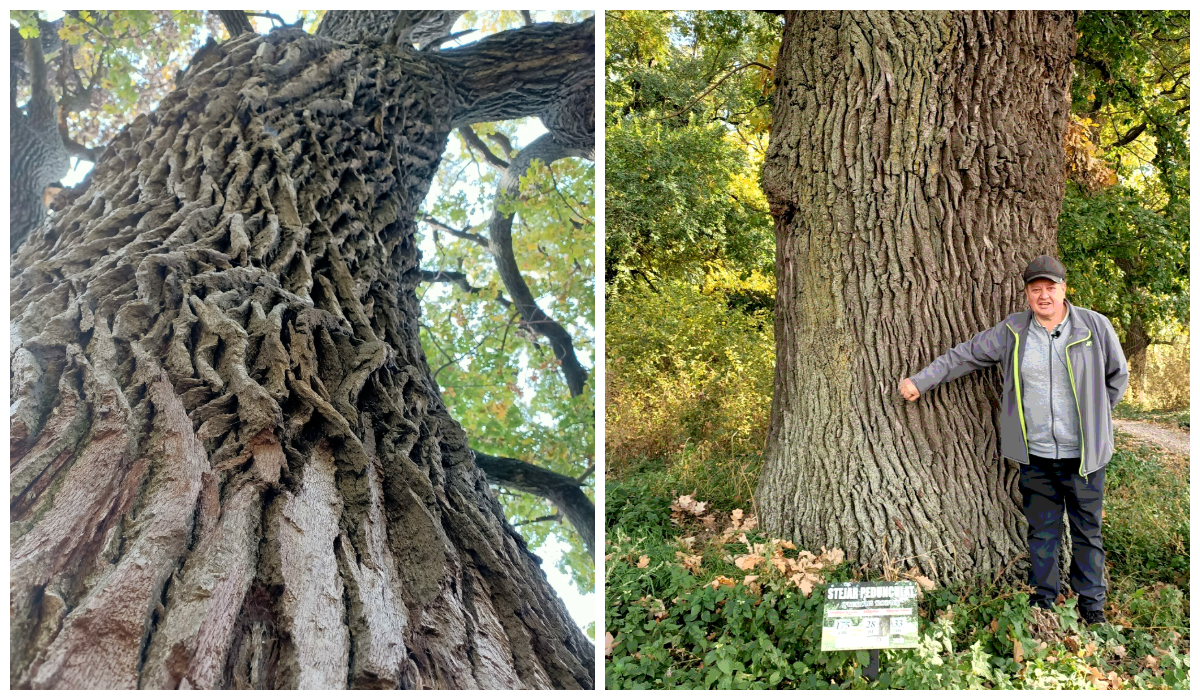

There are around 500 houses in Climăuții de Jos. Many of them still preserve the traditional rural architecture, which can be harnessed for local tourism, according to Tatiana Dudnicenco, PhD and lecturer at the Faculty of Biology and Pedology of the Moldovan State University. In 2015 she published the study “Ecological tourism in the rayons of Șoldănești, Republic of Moldova: problems and perspectives”, in which she also mentioned Climăuți village. The eco-touristic itinerary includes the following places: “Climăuții de Jos” Landscape Reservation, Climăuții de Jos village, Vadul-Rașcov commune, Cușălăuca village, Cușălăuca monastery, “Dobrușa” Landscape Reservation and Dobrușa monastery.

“In Climăuții de Jos the archaic patterns of the Moldovan village still reigns over the life in the village. It can become one of the most representative localities due to its architecture. The peasant houses built in the most classic Moldovan style offer the village a medieval aspect: houses with attics and wide porches, with a central entryway and two rooms – one on the right and the other on the left, and a pantry at the other end of the entryway. Passing through the entangled streets bordered by the low stone walls creates the impression that you are in a real open air ethnographic museum.” writes Tatiana Dudnicenco in her study.

If you are in Climăuți, besides the Nistru river and the traditional houses, you can also see other curious places. You can visit the two water mills. There used to be 25 of them but, over time, they deteriorated and were destroyed.

One of the mill is still standing. Sergiu Costin, the director of the House of Culture in the village of Cot, part of the Climăuții de Jos commune, says that the two floors of the mill used to produce two types of flour. Together with the director of the House of Culture from the neighboring village, Anatolie Lopaci, they pass through the nettle, ignoring the burning sensation and itching, while recounting the taste of the bread baked from the flour grinded at this mill.

Throughout time, the men, both over the age of 50, have roamed the hills far and wide and have gathered many stories. Sergiu tells us that the expression “the water will reach my mill too” comes from the Climăuții de Jos region and it means that “luck will strike me as well.” He says that at the first mill located on the top of the hill, near the Salcia village, the water was stopped. The millers would wait for the water to accumulate and then they would let it flow so it would reach the next mill. At the second mill, the same story. Meanwhile, the other mills were waiting for the water to reach them. “This is why we have this saying: ‘the water will reach my mill too,’” recalls the director of the House of Culture.

The pigeon house

The village is arranged in a Y shape. On one side of the village you can find the Landscape Reservation “Climăuții de Jos” and the red hills, and on the other side the Nistru river flows. If you go further away from the central street and go through the alleyways, you might find yourself believing that you are discovering a different village.

The village is quite peaceful. Only the dogs can sometimes alert their masters of the presence of strangers. When you walk on the hills, the goats will jump higher and higher and a rushing polecat would get out if its burrow.

In the middle of Climăuții de Jos, near the House of Culture, you can find the pigeon house. During the Soviet era, it was used as a produce shop. Today, it serves as home for a few dozen pigeons. The village physical education professor, Iurie, is the one taking care of them. His passion for these birds was inherited from his grandfather, who brought pigeons with him when returning from the war.

The most beautiful of all is the French curly pigeon, a white bird with curly feathers. In his collection there are also Tadjik pigeons, which have a distinctive manner of their flight and the sound made by their wings. Iurie also has messenger pigeons, as well as pigeons weighting almost one kilo – they are used for consumption.

Lida’s Pit – the place where a lovelorn woman took her life

A long time ago, in Vadul-Rașcov and the Rașcov village situated on the other bank of the Nistru river, there used to be open markets and the people from the surroundings would often visit them. So did the daughter of a local merchandise carrier. Liduța and her mother went to the market one day in the neighboring village, Vadul-Rașcov. This is where she met the son of the boyar Stroe and they fell in love. In a time when marriages were more like financial transactions, the boyar from Rașcov forbid their love and sent his son to study in Europe so he would be as further away from Lida as possible. Sad and lonely, the young woman married a boy from the same village. People say that the man resembled perfectly with the boyar’s son. They built a house near the woods, close to the Cușmirca creek.

But after a few years, as it often happens in stories and legends, one rainy evening a traveler knocked on her door and asked to stay overnight. In this stranger she recognized the boy she once fell in love with. After a couple of days, the two started meeting at Țiglău, a steep rock, part of the chain formed following the Sarmatic Sea near the Cușmirca creek. But Lida’s husband found out and killed his wife’s lover.

Legend says that when Lida’s husband was on his deathbed, he told the child they raised together that he is not the father – the boyar’s son from Rașcov was. He also confessed to killing him and burying him under a stone near the Țiglău rock.

When Lida heard her husband’s confession, she ran away and threw herself into the pit formed by the creek. Since then, the pit bears her name. Some say that on the Sânziene Day (Day of the Fairies), Lida’s image appears over the pit. Since then, no woodman would build a house in the forest, only at the edge of the village.

Today, Lida’s Pit is a touristic attraction that catches your eye. It forms a few small waterfalls and gives the forest a special charm. In the summer, tourists come here to listen to the story, see the place and have a rest. Other times, you can catch a few fishermen from the neighboring villages, brave enough to fish in Lida’s Pit.

Years ago, the pit was measuring to 5 meters wide. But, as time passed, it accumulated mud and was never cleaned properly. In order to reach Lida’s Pit, you must take the path alongside Cușmirca creek towards the Climăuții de Jos “mountains”, not towards the Nistru river.

Even if the village has a lot of potential, it is still not harnessed. But you can visit the village, spend the night in a tent on the banks of the Nistru river, catch some fish and cook them on open fire.

Author: Georgeta Carasiucenco

Editor: Marta Sterpu

Culture

The man raising children on Nistru river

Culture

The village of the first astronomer in the Republic of Moldova

Culture

The prodigal son returns and turns his grandparents’ home in a tourist attraction on Nistru river

Reading Time: 7 minutesOn the road towards the school, a well-maintained rural house catches your eye, yellow stags painted on its blue terrace. Behind the house, Nistru river flows peacefully.

Petru Bondari, the owner of the house, comes out into the yard with a plastic bottle. He goes to the spring to bring some water for the tea. He wears a waterproof jacket and hiking boots. Hi walks slowly and looks around with his clear blue eyes, reminiscing about his childhood. He is now 34 years old, and the love for his home village and the passion in his voice makes you believe that everything is possible, wherever you decide to live.

The scrambled eggs

It’s 11 o’clock on a cold winter day. The wind sweeps the snowflakes and the village seems numb. Petru’s childhood is strongly connected to everything related to swimming in the Nistru river, to the cows, to grandma Ileana and the cold plăcinte she used to cook. The children of Pohrebea would run towards Nistru whenever they had the time. Petru remembers the tricks he used in order to have as much time for himself as possible. Once, his mother allowed him to go swimming with the boys only after he would bring her two buckets of horse manure for her to render the oven. “And because I couldn’t find enough manure, I filled the buckets with soil and I placed the manure on top. My mother was amazed that I came back so quickly, and I quickly ran away to the river,” he laughs with nostalgia.

The village of Pohrebea in Dubăsari rayon is inhabited by a few hundred people. It became famous following the “Hodina” festival in 2019. After this event, people became interested in the beautiful landscape of the Nistru river bank. Some even bought houses, which they transformed into guest houses.

When he reaches the spring, Petru bends over and fills the bottle with cold water running from a pipe. A stone wall is built around it, in order to protect it from the rocks falling from up the hill. Even now the locals come and take water from the spring in front of the school close to his grandmother’s house, where he used to come running during the recess and eat something warm and tasty. “The best plăcinte and găluște I had where cooked by grandma Ileana. She would often prepare some scrambled eggs in a hurry. They were so good, that many of my colleagues were dreaming about this dish.” He still remembers the way she was scrambling the eggs so masterfully. “When I was going into the kitchen and see the oil lamp lit, I would know immediately that it’s a Holy day. And it was then when my grandma would cook cold plăcinte, which were incredibly tasty,” recalls Petru about his grandmother, whom he lost when he was a child. Even now, he is still very connected to her. He only knows his grandpa from pictures – he went to war and never came back.

„I felt torn away from everything that makes up a home”

After the death of his grandma, the household became empty. Because it was a difficult period in their lives, his parents decided to sell his grandparents’ house. The new owners left abroad shortly, and grandma Ileana’s house was left unattended. “Every time I was passing by, I felt so much sadness…” Petru admits.

He grew up and went to study Law in Chișinău. At the university he understood that this field is not for him, so he started applying to different programs which offered him the opportunities to leave abroad. “There is this stereotype that if you want to have the life you desire, you must absolutely leave Moldova. I believed it too.” Thus, as a student, he went to Romania, Ukraine, Switzerland, Poland, Belgium, France and the US. In the meantime, he got married.

“Wherever I would end up, I always felt like being torn away from everything that makes up a home,” he admits. Four years ago, Petru returned to Pohrebea. “Nowhere in the world could I feel like home. Only in the village I was born and grew up.” But once he returned, he didn’t find his childhood friends here, ass they all live abroad. This didn’t discourage him. He knew that in Pohrebea he had a place where he can build his life and that he wouldn’t have to start everything from zero. Using his experience, he launched a small business organizing team buildings. The concept is that the activities would take place open air, on the Island of the Cows, the place where the local villagers would take their cows and leave them there from spring till autumn, and in the evening they would go there to milk them. “The cows have everything they need to be happy there, but it is also a very picturesque place,” he smiles, fixing his hair ruffled by the hat.

„La mâca Ileana” guest house

Although years have passed, Petru was still saddened when he would walk near the house where his grandma used to cook him scrambled eggs or the cold plăcinte specially prepared for celebrations. He had some savings and one year ago he contacted the owners of his grandmother’s house. He wanted to buy it no matter the cost. “At first, they told me like 20 times that they wouldn’t sell, then they wouldn’t even answer the phone. But after a while, maybe they thought that they can get rid of me if they ask for a price five times higher than the one they bought it with in the beginning,” he recalls. But in the summer of 2020, both parties signed the sales agreement. Since then, his grandparents’ house started to change to become a guest house. The idea was to open its doors wide to all the people who are in need of peace and quiet, dreamy scrambled eggs and cold plăcinte.

He repaired the house while preserving its authenticity: the roof covered with clay tiles, the whitewashed walls, the colorful ornaments on the outside walls and the old frames with family pictures. Also, he collected old objects in the village, which he arranged in the yard and on the wooden terrace. Thus, in the autumn of 2020, the guest house opened its doors. Here you can find accommodation, but also see how the corn is grinded at the old stone mill Petru took from aunt Dunea. She got it from her mother-in-law, but the original owner is still unknown.

Because the pandemic is still not a thing of the past, the business cannot really flourish, but Petru says that he’s not losing hope. “We have time to make improvements. Everything is new to us, but we adapt,” he says while sitting on the wooden terrace.

The old mill

In the alley there’s aunt Dunea, who is trying to calm down her nephew. The poor little guy was at the dentist earlier and his grandma tries to bribe him with the promise of a fresh colac (ring shaped-bread) and Coca-Cola, as a reward for the teeth he lost so bravely.

“Aunt Dunea, come in… Do you remember the mill you gave me?” asks Petru, while putting his arm over the woman’s shoulders. She is dressed in a black mantle and has a wool scarf over her head. “You want to have a museum here, right?” she jokes timidly. Aunt Dunea looks around till she sees the mill, and memories start coming back to her.

When she was young, her husband, “a strong fellow”, would pour two buckets of wheat and grind them in the mill. They were making flour for bread, plăcinte and cookies. The cold plăcinte were always the stars at every table. She would always share them with the entire neighborhood, with all her relatives. “I have relatives on both banks of Nistru river. When we gathered, the house was full. I went to a few weddings in Transnistria, and they would come to ours. They also make beautiful weddings, very beautiful, I have godchildren there. We call each other, we keep in touch,” she says.

When the people from both banks of Nistru river will visit the “La mâca Ileana” guest house, Petru will grind some corn and make a mămăligă. “We, as common people, don’t have this segregation that one is Moldovan, one is Romanian and the other is Ukrainian or Russian, if they are from Transnistrian region or not,” Petru explains, and aunt Dunea confirms, nodding her head.

The idea of a guest house came to Petru Bondari while also having in mind the revival of the village. From its hills you can see Nistru – a wonderful view attracting tourists. “If the village is visited by more tourists, the locals will have the opportunity to sell their products and stay in the village,” he says. This is why Petru wants to stay in Moldova and develop his business, because “Moldova has potential”.

Moreover, Petru tells us that in the last few years, many houses in Pohrebea were bought by “outsiders”. “Most of them want to transform their houses into vacation homes, where they can spend their weekends and holidays,” he explains.

Pohrebea is a village of legends: kurgans, objects from the Cucuteni-Trypillian civilization and the legend of “Saint Alexei” church are just some of them. In the future, Petru wants to collaborate with entrepreneurs from the left bank of Nistru river, because both sides wish for this to happen. “I had the opportunity on numerous occasions to talk to the people from the Transnistrian region. They told me they would be happy to do things that would improve the situation on their side. Undoubtedly, the desire is there. And when it’s strong enough, everything is possible,” Petru says, while looking at the alleys of the village where he was born, where he grew up and where he wishes to stay.

Author: Eugenia Ciurcă

Editor: Anastasia Condruc