Society

Russia in 2030 will be very different from what most expect

Reading Time: 5 minutesUnlike the citizens of most countries, Russians cannot say what their country will be like only 20 years from now, what will be the names of the rulers, what will be the nature of the political system, what will be the borders of the country, or whether it will even exist as such, according to a Moscow analyst.

By Paul Goble

Unlike the citizens of most countries, Russians cannot say what their country will be like only 20 years from now, what will be the names of the rulers, what will be the nature of the political system, what will be the borders of the country, or whether it will even exist as such, according to a Moscow analyst.

The difficulties Russians now have in that regard, Fedor Krasheninnikov writes in “Svobodnaya pressa” yesterday, can be seen if one compares expectations and realities for three pairs of dates in recent Russian history 1910 and 1930, 1980 and 2000, and even 1990 and today (svpressa.ru/blogs/article/28137/).

It is certainly the case, he says, that “no one in Russia in 1910 could even approximately describe 1930,” but even the latter two pairs are instructive. On the one hand, “the difference between 1980 and 2000” was in some respects even greater, and “even the wisest sovietologists and dissidents were struck by how rapidly reality changed” in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

On the other, “despite all the differences between 1990 and 2010,” Krasheninnikov argues, a revenant from the earlier year “would hardly be surprised” if he found himself in the Russia of today. Everything that has occurred, including the putsch, the collapse of the USSR, and capitalism, would have “seemed to him completely possible.”

The reason for that, the Moscow commentator suggests is that “at the start of major changes when everything around is already beginning to dissolve, people [living in a country like Russia] completely can imagine the most varied development of events and as a result are not surprised” by anything that does occur.

The situation in other countries is very different. There, “living in a stable society which despite all [their] shortcomings, looking at the future all the same does not generate examples of all-embracing destruction.” Instead, people quite reasonably assume that there will be changes at the margin but that the system they are living in will continue much as it is.

That aspect of Russian life has profoundly affected Russian thinking for more than a century, as the comparisons Krasheninnikov suggest. “In 1910, the names Lenin and Kerensky were not very much viewed as future rulers of Russia, and who Stalin was could respond only the rare Bolshevik of an employee of the tsarist secret police.”

“In 1980,” he continues, “few could name the leaders of Russia in 2000.” No one would have mentioned Putin or Kasyanov or Gryzlov. “On the contrary, there were entire echelons of Komsomol and Party officials who sincerely supposed that after the withering away of the Brezhnev Politburo, power would gradually devolve on them.”

Looking out from 2010, the pattern is likely going to be the same, Krasheninnikov insists. Moreover, as he points out, “the structure of power in Russia has changed even more frequently than once every 20 years. If one compares the structure of power in1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010, there is nothing in common, if you think about it.”

Even the top post has changed. “In 1980, the main position was called the CPSU Central Committee General Secretary.” After that, the country’s leader was in 1990, the president of the USSR, in 2000, the president of Russia, and [now] in 2010, the prime minister.” That is dizzying enough.

But there is an even more radical possibility. In 2030, Krasheninnikov writes, “Russia may not exist at all. In any case in its current borders and in its current form.” Many Russians can imagine that the North Caucasus will have gone its own way by then, and the more pessimistic may add the Far East.

Meanwhile, the most thoughtful, he suggests, will recognize that essentially, “only the regions of European Russia are in more or less the same rhythm with Moscow and that only because all the active people [from these areas] long ago already left to life in Moscow and there is no one left to order life differently” in these places.

Elsewhere, the elites have not left, and as a result, “the exclave of Kaliningrad, Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, the Urals, Siberia and the already mentioned Far East … are all living according to their own rhythms and only the improbable efforts at unification of the imperial center still allow one to speak about a certain unity.”

As for himself and allowing for unpredictable chance, Krasheninnikov says that in his view, “after 20 years, the process of the disintegration of the Russian Empire which began in 1917 will end” or be close to it. “Sooner or later,” he says, “Russia will leave its Algeria, the North Caucasus” and consist “only of Moscow and the European part of today’s federation.”

Any effort to prevent this by the use of force, he argues, “will sooner or later produce the oppose effect” of causing even more parts of the country to leave. The only question in that event, Krasheninnikov suggests, is “just how far the pendulum will swing in the opposite direction.”

It is possible that Russia will become a real federation, and it is also possible that it will become a confederation, “a variant of preserving the appearance of a single country despite its factual division into a number of self-administered and in fact independent states.” Such an arrangement might satisfy both elites and the population.

The “most radical of the possible variants,” he continues, would be “the division of the country” into a set of independent states. That would be “possible,” the analyst argues, “only in a situation when the current process of cracking down will last for a long time and thus will make the very idea of a single country hateful for the population.”

But there will be larger forces at work as well. “Considering the demographic situation and the inevitable decline of influence of the petroleum-exporting countries, it is quite naïve to suppose that Russia (or the states arising in its place) will be leaders in world politics and economics.”

In the best sense, Russia “can hope for a more or less prosperous life” having given up its “hegemonic” pretensions. In the worst, it may find itself a battle ground of “authoritarian and aggressive” states, who will “fight among themselves as a result of the [as yet not completed division of] the imperial inheritance.”

Moreover, the situation beyond Russia’s current borders will likely be very different as well. China, now on the rise, is likely to be undermined by that time as a result of its own problems. And “the events in Kyrgyzstan show the rickety quality of the post-Soviet political constructions in Central Asia.”

Krasheninnikov concludes his essay with some remarks about the state of religion in the Russia of 2030. “Twenty years ago,” he writes, “the Russian Orthodox Church,” having emerged from Soviet oppression, looked quite attractive, “especially when compared to the crowds of preachers arriving from the East and the West.”

Now, in 2010, the ROC has become “a semi-state structure, a branch of the powers that be, imposing itself on all of society.” But in 20 years, the situation will certainly be difficult. The ROC even now can’t finance itself, and its actions will alienate ever more parts of the state and society.

As a result, the Russian Orthodox Church will lose a significant part of its current influence,” and into the breach will “inevitably” come Protestants and all the other confessions,” including Islam. “One thing is obvious,” Krasheninnikov writes. The ROC will not be able to exist in its current form.

In short, he concludes, “the only thing Russians can be certain about the future of their country is that it will not be like what people are now saying it will be. Instead, Krasheninnikov says, the situation in 2030 may be worse; it may be better; but beyond any doubt, it will certainly be different.

Society

“They are not needy, but they need help”. How Moldovan volunteers try to create a safe environment for the Ukrainian refugees

At the Government’s ground floor, the phones ring constantly, the laptop screens never reach standby. In one corner of the room there is a logistics planning meeting, someone has a call on Zoom with partners and donors, someone else finally managed to take a cookie and make some coffee. Everyone is exhausted and have sleepy red eyes, but the volunteers still have a lot of energy and dedication to help in creating a safe place for the Ukrainian refugees.

“It’s like a continuous bustle just so you won’t read the news. You get home sometimes and you don’t have time for news, and that somehow helps. It’s a kind of solidarity and mutual support,” says Vlada Ciobanu, volunteer responsible for communication and fundraising.

The volunteers group was formed from the very first day of war. A Facebook page was created, where all types of messages immediately started to flow: “I offer accommodation”, “I want to help”, “I want to get involved”, “Where can I bring the products?”, “I have a car and I can go to the customs”. Soon, the authorities also started asking for volunteers’ support. Now they all work together, coordinate activities and try to find solutions to the most difficult problems.

Is accommodation needed for 10, 200 or 800 people? Do you need transportation to the customs? Does anyone want to deliver 3 tons of apples and does not know where? Do you need medicine or mobile toilets? All these questions require prompt answers and actions. Blankets, sheets, diapers, hygiene products, food, clothes – people bring everything, and someone needs to quickly find ways of delivering them to those who need them.

Sometimes this collaboration is difficult, involves a lot of bureaucracy, and it can be difficult to get answers on time. “Republic of Moldova has never faced such a large influx of refugees and, probably because nobody thought this could happen, a mechanism of this kind of crisis has not been developed. Due to the absence of such a mechanism that the state should have created, we, the volunteers, intervened and tried to help in a practical way for the spontaneous and on the sport solutions of the problems,” mentions Ecaterina Luțișina, volunteer responsible for the refugees’ accommodation.

Ana Maria Popa, one of the founders of the group “Help Ukrainians in Moldova/SOS Українці Молдовa” says that the toughest thing is to find time and have a clear mind in managing different procedures, although things still happen somehow naturally. Everyone is ready to intervene and help, to take on more responsibilities and to act immediately when needed. The biggest challenges arise when it is necessary to accommodate large families, people with special needs, for which alternative solutions must be identified.

Goods and donations

The volunteers try to cope with the high flow of requests for both accommodation and products of all kinds. “It came to me as a shock and a panic when I found out that both mothers who are now in Ukraine, as well as those who found refuge in our country are losing their milk because of stress. We are trying to fill an enormous need for milk powder, for which the demand is high and the stocks are decreasing”, says Steliana, the volunteer responsible for the distribution of goods from the donation centers.

Several centers have been set up to collect donations in all regions of Chisinau, and volunteers are redirecting the goods to where the refugees are. A system for processing and monitoring donations has already been established, while the volunteer drivers take over the order only according to a unique code.

Volunteers from the collection centers also do the inventory – the donated goods and the distributed goods. The rest is transported to Vatra deposit, from where it is distributed to the placement centers where more than 50 refugees are housed.

When they want to donate goods, but they don’t know what would be needed, people are urged to put themselves in the position of refugees and ask themselves what would they need most if they wake up overnight and have to hurriedly pack their bags and run away. Steliana wants to emphasise that “these people are not needy, but these people need help. They did not choose to end up in this situation.”

Furthermore, the volunteer Cristina Sîrbu seeks to identify producers and negotiate prices for products needed by refugees, thus mediating the procurement process for NGOs with which she collaborates, such as Caritas, World Children’s Fund, Polish Solidarity Fund, Lifting hands, Peace Corps and others.

One of the challenges she is facing now is the identifying a mattress manufacturer in the West, because the Moldovan mattress manufacturer that has been helping so far no longer has polyurethane, a raw material usually imported from Russia and Ukraine.

Cristina also needs to find solutions for the needs of the volunteer groups – phones, laptops, gsm connection and internet for a good carrying out of activities.

Hate messages

The most difficult thing for the communication team is to manage the hate messages on the social networks, which started to appear more often. “Even if there is some sort of dissatisfaction from the Ukrainian refugees and those who offer help, we live now in a very diverse society, there are different kind of people, and we act very differently under stress,” said Vlada Ciobanu.

Translation by Cătălina Bîrsanu

Important

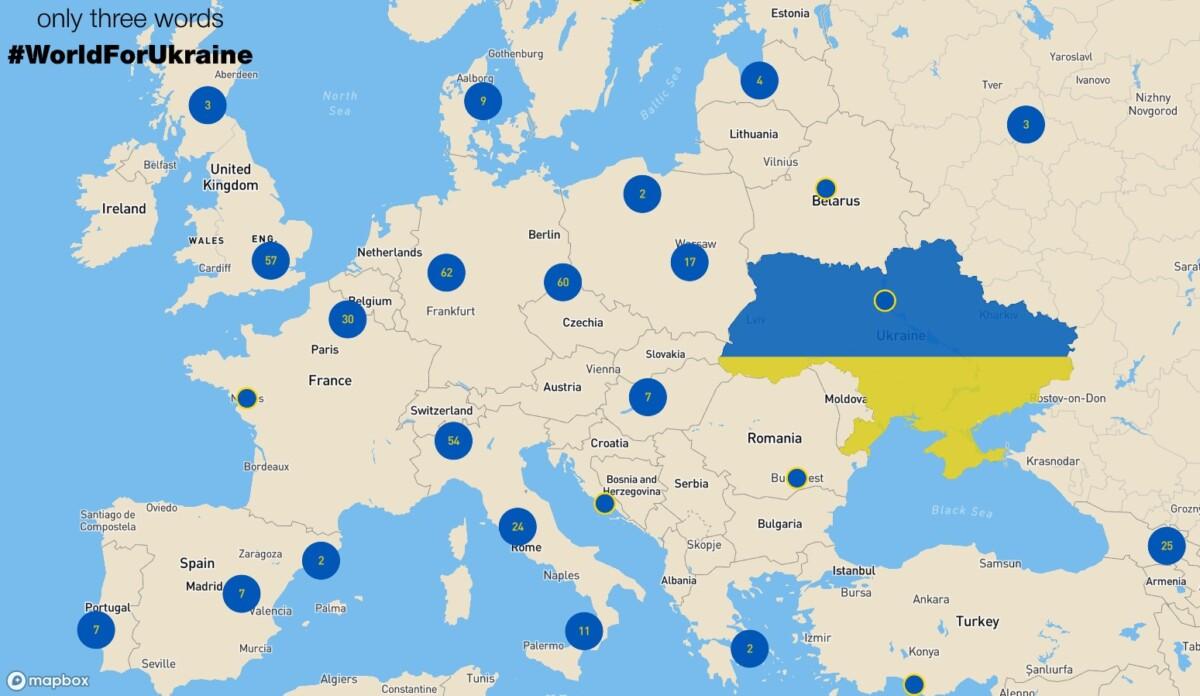

#WorldForUkraine – a map that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against Russian aggression

The international community and volunteers from all over te world have launched #WorldForUkraine as a platform that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against the Russian aggression. In a digital world – it is an interactive map of public support of Ukrainians under the hashtag #WorldForUkraine – rallies, flash mobs, protests around the world. In the physical dimension – it is your opportunity to take to the streets and declare: “No to Putin’s aggression, no to war.”

„Today, along with the political and military support, emotional connection with the civilized world and truthful information are extremely important for Ukraine. The power to do it is in your hands. Join the #WorldForUkraine project and contribute to the victorious battle against the bloodshed inflicted on Ukraine by the aggression of the Russian Federation”, says the „about the project” section of the platform.

Go to the streets — Tell people — Connect and Unite — Become POWERFUL

Volunteers have launched #WorldForUkraine as a platform that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against Russian aggression. In digital world – it is an INTERACTIVE MAP of public support of Ukrainians worldforukraine.net under the hashtag #WorldForUkraine – rallies, flash mobs, protests around the world. In the physical dimension – it is your opportunity to take to the streets and declare: “No to Putin’s aggression, no to war.” There you may find information about past and future rallies in your city in support of Ukraine. This is a permanent platform for Ukrainian diaspora and people all over the world concerned about the situation in Ukraine.

So here’s a couple of things you could do yourself to help:

* if there is a political rally in your city, then participate in it and write about it on social media with geolocation and the hashtag #WorldForUkraine

* if there are no rallies nearby, organize one in support of Ukraine yourself, write about it on social media with geolocation adding the hashtag #WorldForUkraine

The map will add information about gathering by #WorldForUkraine AUTOMATICALLY

Your voice now stronger THAN ever

All rallies are already here: https://worldforukraine.net

Important

How is Moldova managing the big influx of Ukrainian refugees? The authorities’ plan, explained

From 24th to 28th of February, 71 359 Ukrainian citizens entered the territory of Republic of Moldova. 33 173 of them left the country. As of this moment, there are 38 186 Ukrainian citizens in Moldova, who have arrived over the past 100 hours.

The Moldovan people and authorities have organized themselves quickly from the first day of war between Russia and Ukraine. However, in the event of a prolonged armed conflict and a continuous influx of Ukrainian refugees, the efforts and donations need to be efficiently managed. Thus, we inquired about Moldova’s long-term plan and the state’s capacity to receive, host, and treat a bigger number of refugees.

On February 26th, the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Moldova approved the Regulation of organization and functioning of the temporary Placement Center for refugees and the staffing and expenditure rules. According to the Regulation, the Centers will have the capacity of temporary hosting and feeding at least 20 persons, for a maximum of 3 months, with the possibility of extending this period. The Centers will also offer legal, social, psychological, and primary medical consultations to the refugees. The Center’s activity will be financed from budget allocations, under Article 19 of Provision no. 1 of the Exceptional Situations Commission from February 24th, 2022, and from other sources of funding that do not contravene applicable law.

The Ministry of Inner Affairs and the Government of Moldova facilitated the organization of the volunteers’ group “Moldova for Peace”. Its purpose is to receive, offer assistance and accommodation to the Ukrainian refugees. The group is still working on creating a structure, registering and contacting volunteers, etc. It does not activate under a legal umbrella.

Lilia Nenescu, one of the “Moldova for Peace” volunteers, said that the group consists of over 20 people. Other 1700 registered to volunteer by filling in this form, which is still available. The group consists of several departments:

The volunteers’ department. Its members act as fixers: they’re responsible for connecting the people in need of assistance with the appropriate department. Some of the volunteers are located in the customs points. “The Ministry of Inner Affairs sends us every day the list of the customs points where our assistance is needed, and we mobilize the volunteers”, says Lilia Nenescu.

The Goods Department manages all the goods donated by the Moldavian citizens. The donations are separated into categories: non-perishable foods and non-food supplies. The volunteers of this department sort the goods into packages to be distributed.

The Government intends to collect all the donations in four locations. The National Agency for Food Safety and the National Agency for Public Health will ensure mechanisms to confirm that all the deposited goods comply with safety and quality regulations.

The Service Department operates in 4 directions and needs the volunteer involvement of specialists in psychology, legal assistance (the majority of the refugees only have Ukrainian ID and birth certificates of their children); medical assistance; translation (a part of the refugees are not Ukrainian citizens).

According to Elena Mudrîi, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Health, so far there is no data about the number of Covid-19 positive refugees. She only mentioned two cases that needed outpatient medical assistance: a pregnant woman and the mother of a 4-day-old child.

The Accommodation Department. The volunteers are waiting for the centralized and updated information from the Ministry of Labor about the institutions offering accommodation, besides the houses offered by individuals.

The Transport Department consists of drivers organized in groups. They receive notifications about the number of people who need transportation from the customs points to the asylum centers for refugees.

The municipal authorities of Chișinău announced that the Ukrainian children refugees from the capital city will be enrolled in educational institutions. The authorities also intend to create Day-Care Centers for children, where they will be engaged in educational activities and will receive psychological assistance. Besides, the refugees from the municipal temporary accommodation centers receive individual and group counseling.

In addition to this effort, a group of volunteers consisting of Ana Gurău, Ana Popapa, and Andrei Lutenco developed, with the help of Cristian Coșneanu, the UArefugees platform, synchronized with the responses from this form. On the first day, 943 people offered their help using the form, and 110 people asked for help. According to Anna Gurău, the volunteers communicate with the Government in order to update the platform with the missing data.

Translation from Romanian by Natalia Graur